Location

Giza, Egypt

Program

Museum

Size

100,000 square meters

Dates

2002

Key Staff

Eric McNevin, Sophie Frank, Scott Nakao, Jose Herrasti

The Grand Egyptian Museum is a unique repository of culture — religious, artistic, linguistic, historic. Twenty-first century Egypt, the inheritor of a 3,000 year old cultural ethos, has the responsibility to continue to explain the durability, the power, and the continuing mystery of the Egyptian story to the contemporary world. How to give this story an architectural form is the question.

The proposal presents historic Egyptian culture from multiple vantage points in order to issue that its contents and seen and understood in a variety of ways.

The organizational conception for the project – the sequence for enjoying the exhibits; the method for assembling the exhibits; the means to continue to study and discuss the museum’s contents — will be clearly legible and readily accessible to the public, staff, and scholarly constituencies who will use the building. Multiple spatial configurations and flexible media venues will facilitate the most thorough representation of Egypt’s cultural history.

The architecture will both look to the future, and acknowledge the past, in order to communicate the continuing vitality and relevance of Egypt’s built history. Both the size of the current collection, and the definition of Egyptian history, will likely change over time. Newspaper headlines regularly confirm important new archaeological discoveries and, as a consequence, new theories that account for that culture will be proposed. Egypt’s historic record and its interpretation are subject to revision. The Grand Museum will also allow for organizational change as change is required to accommodate new exhibitions and new points of view.

The project site adjoins the Cairo-Alexandria desert road, and is north-west of the Pyramids and the Sphinx. Proximity to this most powerful example of the Museum’s essential subject matter associates the site with the longevity of the cultural achievement that belongs uniquely to Egypt. The site area itself contains a portion of the history the building will represent.

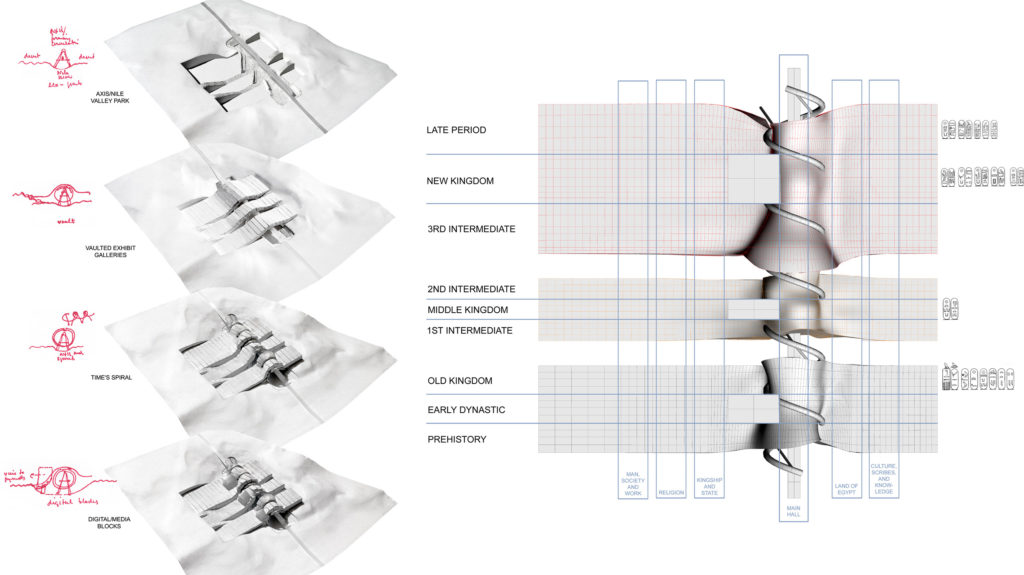

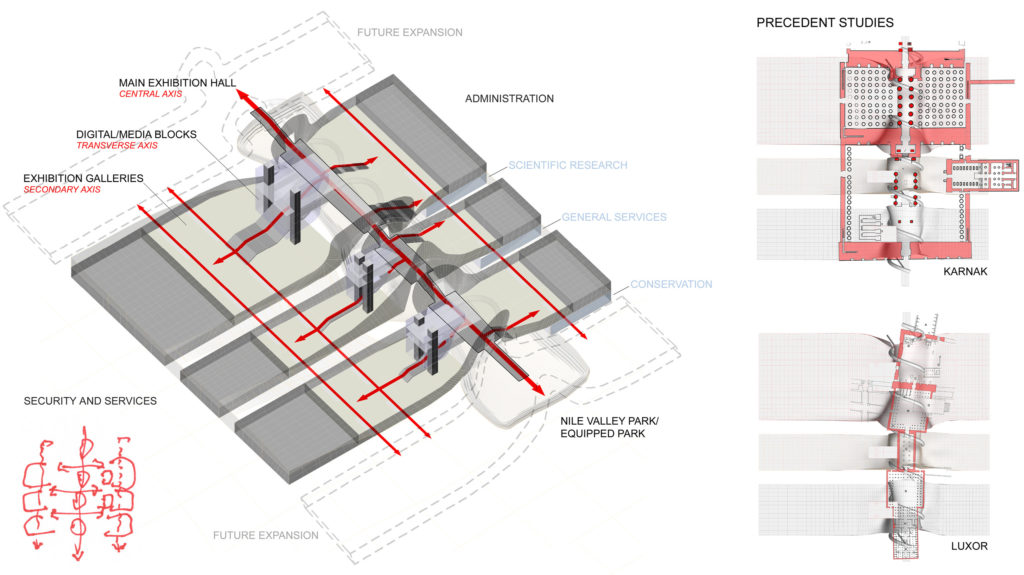

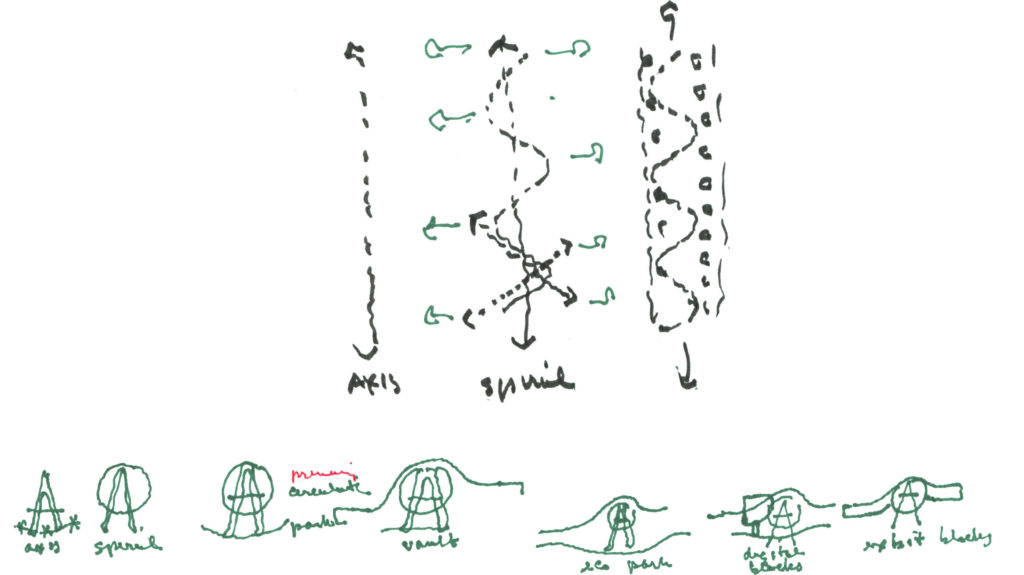

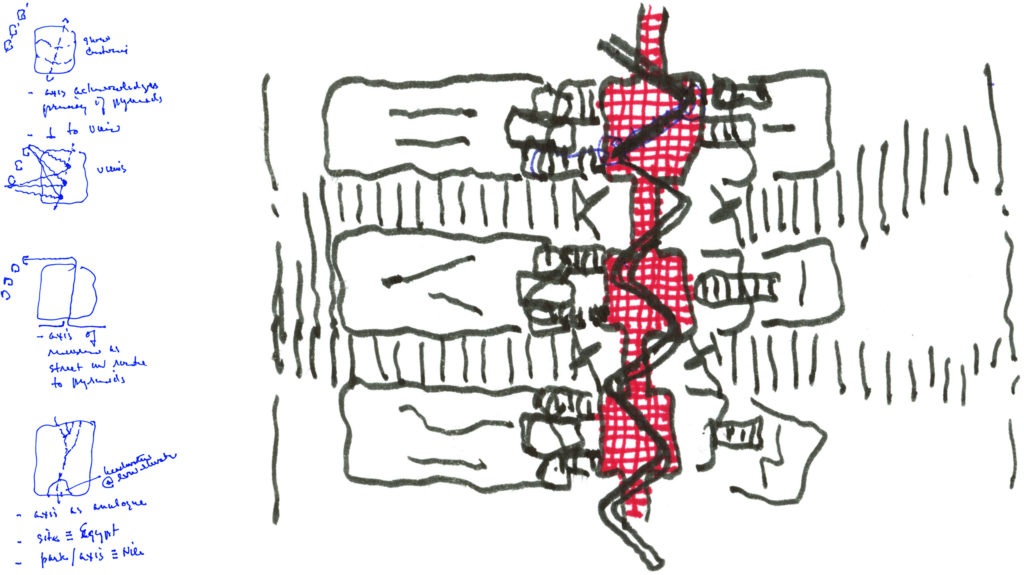

A simple line is drawn on the site, precisely replicating the east-west orientation of the pyramids. This idealized line, the axis of the rising and setting sun, becomes the primary pedestrian route through the project. The Museum axis confirms the proprietary order of the celestial premise of the pyramids’ site plan.

The new axial line connects the residential area south of the site with the Cairo-Alexandria Road. In this sense the Museum project becomes both building and city infrastructure. The new axis connects the south and north perimeters of the site and encourages pedestrians to move through the “Museum street” on the way to visits to the Pyramids and the Sphinx.

The project site is imagined as a microcosm of the country of Egypt, with two primary geographical features: the desert and the Nile River. The Sand Dune Park, an analogy for Egypt’s desert, will occupy the largest part of the unbuilt portion of the site. A central, man-made river, with landscape, exhibits, and performance areas surrounds the axis as it crosses the site, forming an eco-park analogue of the Nile River basin and surrounding desert.

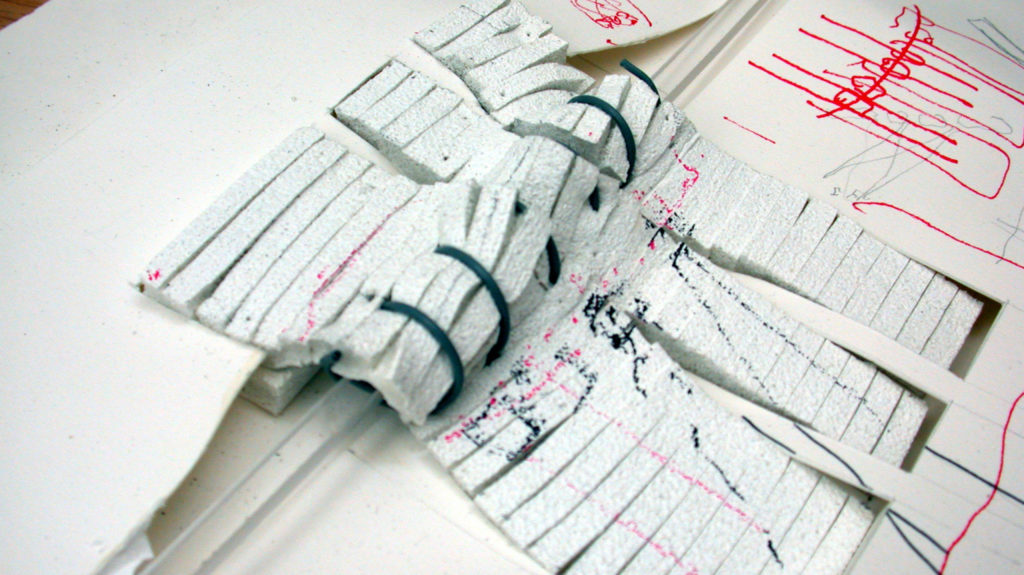

The design concept organizes public movement through a diverse range of exhibits and spatial types. The primary axis is conceived as a processional spiral, in the tradition of the central axes of Luxor and Karnak. The spiral metaphor suggests a coalescing of time and history – infinite and open-ended. The space is a sequence of curving steel pipes, supported by steel columns. Beams span between the columns to support the main floor and additional floors, above as needed. In the tradition of Egypt’s colossi (eg. Abu Simbel) the scale and content of the spiral gallery are imposing.

A vault of varying dimensions covers the axis. The vault encloses the spiral gallery. The cosmological analogy for the vault is the Egyptian deity Nut, whose form is the celestial canopy, which daily gives birth to Ra —the Sun. The life, spirit and mystery of that daily re-birth will be manifest in the spatial power of the walk along the axis under the vaulted roof. The vault varies in size to accommodate the largest possible variety of events. The vault is usable for exhibition hangings, and as a projection surface, providing cinematic information and entertainment.

Adjoining the axis are the blocks, rectangular volumes of various sizes. The blocks are positioned along the axis to be used in concert with the exhibits to provide additional space as required (in the Egyptian tradition of secondary spaces, disposed along an axis. e.g. Karnak, Luxor, Abu Simbel) to accommodate film, video, or interactive media productions or more conventional exhibit support venues. The block buildings can be sub-divided to present Egypt’s dynastic chronology in sequence, or for changing exhibitions, and may be increased in size or number [more can be built] as the collection grows along the axis [which may also be extended in length]. The digital blocks can hold seats in a raked theatre configuration, more flexibly on flat floors, or can be sub-divided into individual or group inter-active stations for data retrieving or viewing of information in the museum collection or from external sources, world-wide. The digital blocks can also be used for public lectures or small-scale performances. The blocks connect to the main axis with stair and escalator galleries, perpendicular to the spiral gallery.

The temple of Hatshepsut is a prominent example of Egyptian funerary architecture. The section relationship between the axial gallery of the Museum and the adjacent blocks through a sequence of descending floor plains, is spatially analogous to those well-known terraces in the Valley of the Kings. The public will move first along the main axis which terraces from north-east to south-west to conform to the sloping topography of the site, then perpendicular to the primary axis, stepping down in the blocks.

Media events and large installations are suspended from the vault. Stationary exhibits and media stations line the axis perimeters. Directly below the axis, is the open-air, eco-river park, useable for performances and outdoor exhibitions. On either side of the axis escalators and stairs to the installations and exhibits in the galleries are positioned in the digital blocks. The Pyramids are in view to the south-west, as museum goers descend within the blocks. Terraces on the blocks’ roofs provide space for outdoor installation. A floor level can be added along the main axis, accessed by ramps. Restoration laboratories for new archaeological discoveries are positioned at the base of the exhibit blocks.

In his argument for a “Museum without Walls”, Andre Malraux reminded us that most of what is considered art in the contemporary world was not understood as art by the cultures that produced it. For 3,000 years Egypt invented and sustained one of the most compelling cultures in history. We owe that culture a Museum where the re-production of that history is equally powerful, and unique. Using the most diverse presentation means in an architecture which has the capacity to continue to be remodeled, Egypt’s (and the world’s) Grand(est) Museum will bring new form and new life to Egypt’s cultural history.

Nut will again give birth to Ra.